Photos from Petrology field trip to the

Adirondack Mountains - October 2004

Kurt

Friehauf

We started at the Barton garnet deposit

We started at the Barton garnet deposit

Panning for garnet gems. The

Barton family are truly excellent citizens! They are a credit to

mining and the Adirondack region. They do a lot of work with

school groups, run a tight and clean ship, and produce great

product. Great people!

Panning for garnet gems. The

Barton family are truly excellent citizens! They are a credit to

mining and the Adirondack region. They do a lot of work with

school groups, run a tight and clean ship, and produce great

product. Great people!

Garnet porphyroblasts with

hornblende rims in metamorphosed metaolivine gabbro.

Garnet porphyroblasts with

hornblende rims in metamorphosed metaolivine gabbro.

Zach posing for scale with garnets

Zach posing for scale with garnets

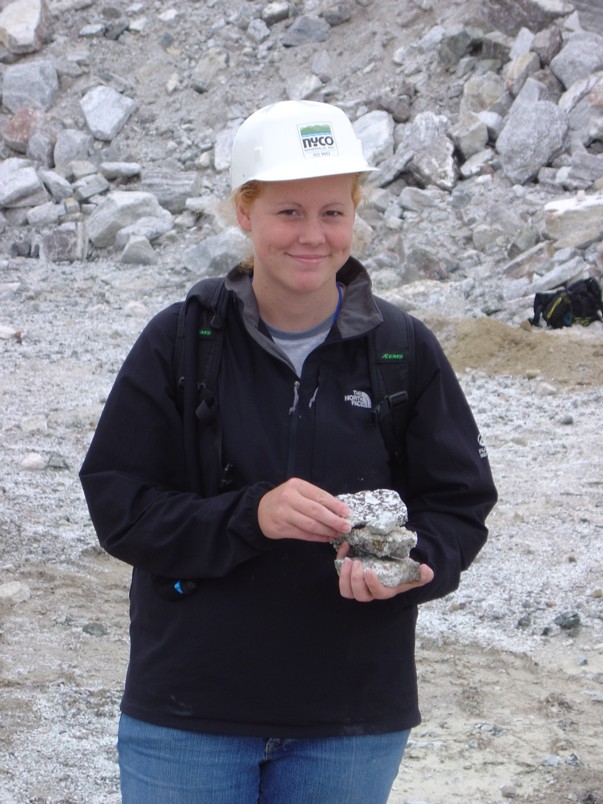

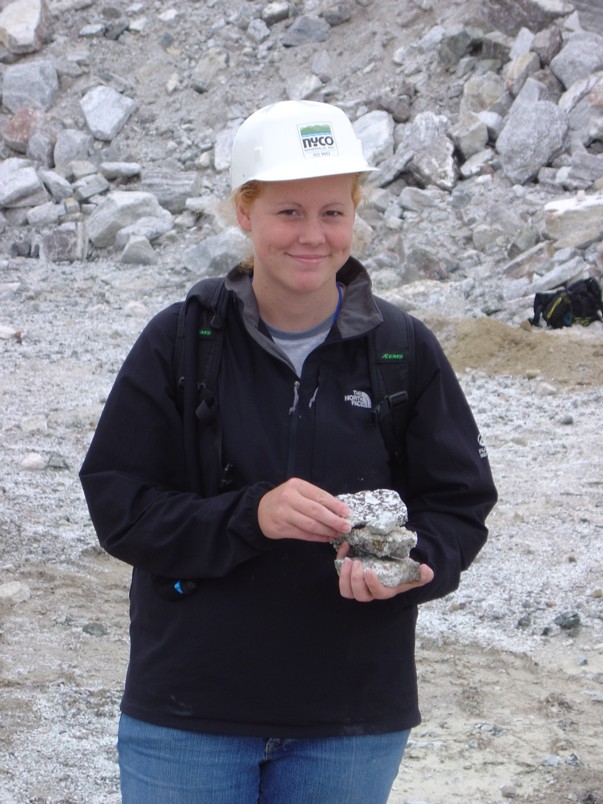

Wollastonite is used in a variety

of everyday products, including a sort of microscopic re-bar in

plastics! How massive deposits of wollastonite form is the puzzle

students must solve here!

Wollastonite is used in a variety

of everyday products, including a sort of microscopic re-bar in

plastics! How massive deposits of wollastonite form is the puzzle

students must solve here!

Josh showing good hand lens

technique. Head held high to allow more light - lens just at

eyelash distance from his eye - eye that's not looking through the loop

is open and relaxed - no facial scrunching. Good job!

Josh showing good hand lens

technique. Head held high to allow more light - lens just at

eyelash distance from his eye - eye that's not looking through the loop

is open and relaxed - no facial scrunching. Good job!

Andy was such a professional and a

great guy. It's both very happy and quite sad for professors when

good students graduate. I miss a lot of them.

Andy was such a professional and a

great guy. It's both very happy and quite sad for professors when

good students graduate. I miss a lot of them.

We camp at night to keep costs

down. It's tricky finding campgrounds that are open after Labor

Day, but we seem to manage.

We camp at night to keep costs

down. It's tricky finding campgrounds that are open after Labor

Day, but we seem to manage.

I used to run this fieldtrip in

the late spring, but the snow caused some problems. Moving it to

fall creates different problems, but was overall a good idea.

I used to run this fieldtrip in

the late spring, but the snow caused some problems. Moving it to

fall creates different problems, but was overall a good idea.

Charyn always cooked up something

wonderfully aromatic and different. I'm afraid I usually just

throw together spaghetti, burritos, or other very quick and simple food

when I cook for the group. This year will be different,

though! I have big plans!

Charyn always cooked up something

wonderfully aromatic and different. I'm afraid I usually just

throw together spaghetti, burritos, or other very quick and simple food

when I cook for the group. This year will be different,

though! I have big plans!

Anorthosite - a special igneous

rock characteristic of the Adirondacks - warrants close

inspection. These students are not kissing the rock, rather

they're looking at the mineral crystals with high powered magnifying

lenses identical the the jewlers loops you might have seen in diamond

store.

Anorthosite - a special igneous

rock characteristic of the Adirondacks - warrants close

inspection. These students are not kissing the rock, rather

they're looking at the mineral crystals with high powered magnifying

lenses identical the the jewlers loops you might have seen in diamond

store.

It's always good to see thoughtful

discussion on the outcrop. Here, students discuss the different

types of anorthosite found in the outcrop and the relative timing of

the injection of different magmas.

It's always good to see thoughtful

discussion on the outcrop. Here, students discuss the different

types of anorthosite found in the outcrop and the relative timing of

the injection of different magmas.

For me, this will always be the Outcrop

of

Tears. The

first group I took up here didn't like this outcrop at all because I

asked them to precisely estimate the proportions of different minerals

in the igneous rock. It was a fiasco! Since then, I've

taken two other groups and no one's had problems doing it.

For me, this will always be the Outcrop

of

Tears. The

first group I took up here didn't like this outcrop at all because I

asked them to precisely estimate the proportions of different minerals

in the igneous rock. It was a fiasco! Since then, I've

taken two other groups and no one's had problems doing it.

Look ma! No tears!

This group did a great job on this outcrop!

Look ma! No tears!

This group did a great job on this outcrop!

In addition to getting right up to

the rock, it's also important to step back and try to see the big

picture. That's a lesson I learned from one of the smartest guys

I've ever met (Lans Taylor - extraordinarily nice guy and so smart it

was spooky!).

In addition to getting right up to

the rock, it's also important to step back and try to see the big

picture. That's a lesson I learned from one of the smartest guys

I've ever met (Lans Taylor - extraordinarily nice guy and so smart it

was spooky!).

Zach and Josh trying to work out

the rock type. The debate here was in the identity of the dark

colored mineral - biotite, hornblende, pyroxene, or olivine? The

Adirondacks have some unusual rocks, so it's a good question!

Zach and Josh trying to work out

the rock type. The debate here was in the identity of the dark

colored mineral - biotite, hornblende, pyroxene, or olivine? The

Adirondacks have some unusual rocks, so it's a good question!

I guess I must have interupted

them in their work to warrant scowls like this! It's good to see

people so focused on their work!

I guess I must have interupted

them in their work to warrant scowls like this! It's good to see

people so focused on their work!

The Lion Mountain iron deposit was

mined long, long ago, but is now closed. It's a good example,

though, of granitic gneiss hosted iron ores of the Adirondacks.

The Lion Mountain iron deposit was

mined long, long ago, but is now closed. It's a good example,

though, of granitic gneiss hosted iron ores of the Adirondacks.

After studying the iron ores in

the pit, we stop to visit the giant pile of sand made from ground up

ore. It's an amazing pile!!

After studying the iron ores in

the pit, we stop to visit the giant pile of sand made from ground up

ore. It's an amazing pile!!

Three students climbed to the top

to illustrate how big this pile of sand really is.

Three students climbed to the top

to illustrate how big this pile of sand really is.

Patroling campsite for litter -

leave the site cleaner

than you find it!

Patroling campsite for litter -

leave the site cleaner

than you find it!

The fayalite granite is a neat

stop. Fayalite is a mineral belonging to the olivine mineral

family. Olivine is typical of very iron-magnesium rich rocks more

characteristic of the ocean floors. Granite, on the other hand,

is iron and magnesium-poor and so only very, very, very rarely contains

olivine. There are some chemical reasons for this, but I can't

tell you on this website or else my students will know the answer

before they get to the outcrop. One big part of fieldtrips with

me is learning to make careful observations. The other big part

of fieldtrips with me, though, is thinking about rocks in terms of

process while you're on the outcrop.

The fayalite granite is a neat

stop. Fayalite is a mineral belonging to the olivine mineral

family. Olivine is typical of very iron-magnesium rich rocks more

characteristic of the ocean floors. Granite, on the other hand,

is iron and magnesium-poor and so only very, very, very rarely contains

olivine. There are some chemical reasons for this, but I can't

tell you on this website or else my students will know the answer

before they get to the outcrop. One big part of fieldtrips with

me is learning to make careful observations. The other big part

of fieldtrips with me, though, is thinking about rocks in terms of

process while you're on the outcrop.

This outcrop is half red and half

gray. What causes this difference?

This outcrop is half red and half

gray. What causes this difference?

Lunchtime!

Lunchtime!

Mylonite is a layered rock that

forms by crushing of the mineral grains when the rock is sheared.

The two main zones of the Adirondack region are separated by a mylonite

zone, suggesting one of the zones slid down along a shear zone from a

different place.

Mylonite is a layered rock that

forms by crushing of the mineral grains when the rock is sheared.

The two main zones of the Adirondack region are separated by a mylonite

zone, suggesting one of the zones slid down along a shear zone from a

different place.

Andy points out the direction of

the lineation in the mylonite.

Andy points out the direction of

the lineation in the mylonite.

Proud of their oriented sample,

Josh and Andy pose by their treasure. An oriented sample is one

which the geologist carefully records the orientation of before

bagging. This allows the geologist to orient the sample in the

exact same direction, tilt, etc. back in the lab. Some mineral

textures tell us the direction a rock was smeared/squished/etc.

We need to be able to analyze those mineral textures knowing their

orientation!

Proud of their oriented sample,

Josh and Andy pose by their treasure. An oriented sample is one

which the geologist carefully records the orientation of before

bagging. This allows the geologist to orient the sample in the

exact same direction, tilt, etc. back in the lab. Some mineral

textures tell us the direction a rock was smeared/squished/etc.

We need to be able to analyze those mineral textures knowing their

orientation!

Cooling off in Cranberry Lake

after a day of rock study. The temperature was actually quite

cool, but a dip in a mountain lake is tough to pass up!

Cooling off in Cranberry Lake

after a day of rock study. The temperature was actually quite

cool, but a dip in a mountain lake is tough to pass up!

It's good to wake up early so you

can see the sun rise.

It's good to wake up early so you

can see the sun rise.

The world is an incredibly

beautiful place, isn't it?

The world is an incredibly

beautiful place, isn't it?

Migmatite is a rock that forms

when rocks are buried so deeply and heated so much that they start to

melt. The liquid migrates into swirly zones like the ones Dana's

modeling here.

Migmatite is a rock that forms

when rocks are buried so deeply and heated so much that they start to

melt. The liquid migrates into swirly zones like the ones Dana's

modeling here.

A basalt dike cuts across a

meionitic marble in the northwest Adirondacks. Rocks in the

northwest Adirondack lowlands are mostly metamorphosed sedimentary

rocks. The basalt formed much, much later when molten magma

injected into fractures. Such basalt dikes are commonly

associated with rifting, although I don't know if this particular dike

formed during the Neoproterozoic rifting, or the late Triassic rifting

event.

A basalt dike cuts across a

meionitic marble in the northwest Adirondacks. Rocks in the

northwest Adirondack lowlands are mostly metamorphosed sedimentary

rocks. The basalt formed much, much later when molten magma

injected into fractures. Such basalt dikes are commonly

associated with rifting, although I don't know if this particular dike

formed during the Neoproterozoic rifting, or the late Triassic rifting

event.

The Train Wreck - a very famous

outcrop in the Adirondack region. The dark blocks of garnet were

once a cotinuous, albeit brittle bed of rock. The surrounding

gray swirly stuff is marble. In metamorphic temperatures and

pressures, the marble flows like toothpaste, but the brittle garnet

fractures into pieces, which are smeared out to to geologic forces.

The Train Wreck - a very famous

outcrop in the Adirondack region. The dark blocks of garnet were

once a cotinuous, albeit brittle bed of rock. The surrounding

gray swirly stuff is marble. In metamorphic temperatures and

pressures, the marble flows like toothpaste, but the brittle garnet

fractures into pieces, which are smeared out to to geologic forces.

Glacial striations formed when the

giant continental glacier of the last ice age scraped across these

rocks 20,000 years ago. The scratches tell the direction the ice

was flowing.

Glacial striations formed when the

giant continental glacier of the last ice age scraped across these

rocks 20,000 years ago. The scratches tell the direction the ice

was flowing.

The Steer's Head outcrop - studing

chemical reaction rims that form when rocks of different compositions

are in contact with one another during metamorphism. Students

here must first identify the minerals present and then deduce what

chemical reactions took place. Again, I can't tell you the answer

right here in case future students are reading this!

The Steer's Head outcrop - studing

chemical reaction rims that form when rocks of different compositions

are in contact with one another during metamorphism. Students

here must first identify the minerals present and then deduce what

chemical reactions took place. Again, I can't tell you the answer

right here in case future students are reading this!

Close-ups of the reaction rims

Close-ups of the reaction rims

Talking about the Balmat zinc

deposit with Bill DeLorraine - a geologist working at the mine.

Bill's incredibly sharp - the folks at HudBay Minerals, Inc. are lucky

to have such a smart and experienced guy working for them. Here,

the class poses by the three dimensional mine model that shows the ways

the orebodies twist and turn deep underground. We were not able

to tour underground, though, because the mine was closed down.

The Balmat mine, being a smaller mine, must open and close depending on

the price of zinc metal. Opening and closing a mine's opperations

is an expensive endeavor, so it's not a decision made lightly.

They keep the mine pumped dry, though, during the time they're closed

down, which dramatically reduces the start up costs.

Talking about the Balmat zinc

deposit with Bill DeLorraine - a geologist working at the mine.

Bill's incredibly sharp - the folks at HudBay Minerals, Inc. are lucky

to have such a smart and experienced guy working for them. Here,

the class poses by the three dimensional mine model that shows the ways

the orebodies twist and turn deep underground. We were not able

to tour underground, though, because the mine was closed down.

The Balmat mine, being a smaller mine, must open and close depending on

the price of zinc metal. Opening and closing a mine's opperations

is an expensive endeavor, so it's not a decision made lightly.

They keep the mine pumped dry, though, during the time they're closed

down, which dramatically reduces the start up costs.

Hunting for marble outcrops in the

Adirondack jungle.

Hunting for marble outcrops in the

Adirondack jungle.

Some strange features in the

marble. The locations of these features is a secret - they are

pretty incredible and should not be disturbed, as you well know if you

recognize what they are!

Some strange features in the

marble. The locations of these features is a secret - they are

pretty incredible and should not be disturbed, as you well know if you

recognize what they are!

.

We started at the Barton garnet deposit

We started at the Barton garnet deposit Panning for garnet gems. The

Barton family are truly excellent citizens! They are a credit to

mining and the Adirondack region. They do a lot of work with

school groups, run a tight and clean ship, and produce great

product. Great people!

Panning for garnet gems. The

Barton family are truly excellent citizens! They are a credit to

mining and the Adirondack region. They do a lot of work with

school groups, run a tight and clean ship, and produce great

product. Great people!

Garnet porphyroblasts with

hornblende rims in metamorphosed metaolivine gabbro.

Garnet porphyroblasts with

hornblende rims in metamorphosed metaolivine gabbro. Zach posing for scale with garnets

Zach posing for scale with garnets

Wollastonite is used in a variety

of everyday products, including a sort of microscopic re-bar in

plastics! How massive deposits of wollastonite form is the puzzle

students must solve here!

Wollastonite is used in a variety

of everyday products, including a sort of microscopic re-bar in

plastics! How massive deposits of wollastonite form is the puzzle

students must solve here!

Josh showing good hand lens

technique. Head held high to allow more light - lens just at

eyelash distance from his eye - eye that's not looking through the loop

is open and relaxed - no facial scrunching. Good job!

Josh showing good hand lens

technique. Head held high to allow more light - lens just at

eyelash distance from his eye - eye that's not looking through the loop

is open and relaxed - no facial scrunching. Good job!

Andy was such a professional and a

great guy. It's both very happy and quite sad for professors when

good students graduate. I miss a lot of them.

Andy was such a professional and a

great guy. It's both very happy and quite sad for professors when

good students graduate. I miss a lot of them. We camp at night to keep costs

down. It's tricky finding campgrounds that are open after Labor

Day, but we seem to manage.

We camp at night to keep costs

down. It's tricky finding campgrounds that are open after Labor

Day, but we seem to manage.

I used to run this fieldtrip in

the late spring, but the snow caused some problems. Moving it to

fall creates different problems, but was overall a good idea.

I used to run this fieldtrip in

the late spring, but the snow caused some problems. Moving it to

fall creates different problems, but was overall a good idea. Charyn always cooked up something

wonderfully aromatic and different. I'm afraid I usually just

throw together spaghetti, burritos, or other very quick and simple food

when I cook for the group. This year will be different,

though! I have big plans!

Charyn always cooked up something

wonderfully aromatic and different. I'm afraid I usually just

throw together spaghetti, burritos, or other very quick and simple food

when I cook for the group. This year will be different,

though! I have big plans!

Anorthosite - a special igneous

rock characteristic of the Adirondacks - warrants close

inspection. These students are not kissing the rock, rather

they're looking at the mineral crystals with high powered magnifying

lenses identical the the jewlers loops you might have seen in diamond

store.

Anorthosite - a special igneous

rock characteristic of the Adirondacks - warrants close

inspection. These students are not kissing the rock, rather

they're looking at the mineral crystals with high powered magnifying

lenses identical the the jewlers loops you might have seen in diamond

store.

It's always good to see thoughtful

discussion on the outcrop. Here, students discuss the different

types of anorthosite found in the outcrop and the relative timing of

the injection of different magmas.

It's always good to see thoughtful

discussion on the outcrop. Here, students discuss the different

types of anorthosite found in the outcrop and the relative timing of

the injection of different magmas.

For me, this will always be the Outcrop

of

Tears. The

first group I took up here didn't like this outcrop at all because I

asked them to precisely estimate the proportions of different minerals

in the igneous rock. It was a fiasco! Since then, I've

taken two other groups and no one's had problems doing it.

For me, this will always be the Outcrop

of

Tears. The

first group I took up here didn't like this outcrop at all because I

asked them to precisely estimate the proportions of different minerals

in the igneous rock. It was a fiasco! Since then, I've

taken two other groups and no one's had problems doing it.

Look ma! No tears!

This group did a great job on this outcrop!

Look ma! No tears!

This group did a great job on this outcrop! In addition to getting right up to

the rock, it's also important to step back and try to see the big

picture. That's a lesson I learned from one of the smartest guys

I've ever met (Lans Taylor - extraordinarily nice guy and so smart it

was spooky!).

In addition to getting right up to

the rock, it's also important to step back and try to see the big

picture. That's a lesson I learned from one of the smartest guys

I've ever met (Lans Taylor - extraordinarily nice guy and so smart it

was spooky!).

Zach and Josh trying to work out

the rock type. The debate here was in the identity of the dark

colored mineral - biotite, hornblende, pyroxene, or olivine? The

Adirondacks have some unusual rocks, so it's a good question!

Zach and Josh trying to work out

the rock type. The debate here was in the identity of the dark

colored mineral - biotite, hornblende, pyroxene, or olivine? The

Adirondacks have some unusual rocks, so it's a good question!

I guess I must have interupted

them in their work to warrant scowls like this! It's good to see

people so focused on their work!

I guess I must have interupted

them in their work to warrant scowls like this! It's good to see

people so focused on their work!

The Lion Mountain iron deposit was

mined long, long ago, but is now closed. It's a good example,

though, of granitic gneiss hosted iron ores of the Adirondacks.

The Lion Mountain iron deposit was

mined long, long ago, but is now closed. It's a good example,

though, of granitic gneiss hosted iron ores of the Adirondacks.

After studying the iron ores in

the pit, we stop to visit the giant pile of sand made from ground up

ore. It's an amazing pile!!

After studying the iron ores in

the pit, we stop to visit the giant pile of sand made from ground up

ore. It's an amazing pile!!

Three students climbed to the top

to illustrate how big this pile of sand really is.

Three students climbed to the top

to illustrate how big this pile of sand really is.  Patroling campsite for litter -

leave the site cleaner

than you find it!

Patroling campsite for litter -

leave the site cleaner

than you find it! The fayalite granite is a neat

stop. Fayalite is a mineral belonging to the olivine mineral

family. Olivine is typical of very iron-magnesium rich rocks more

characteristic of the ocean floors. Granite, on the other hand,

is iron and magnesium-poor and so only very, very, very rarely contains

olivine. There are some chemical reasons for this, but I can't

tell you on this website or else my students will know the answer

before they get to the outcrop. One big part of fieldtrips with

me is learning to make careful observations. The other big part

of fieldtrips with me, though, is thinking about rocks in terms of

process while you're on the outcrop.

The fayalite granite is a neat

stop. Fayalite is a mineral belonging to the olivine mineral

family. Olivine is typical of very iron-magnesium rich rocks more

characteristic of the ocean floors. Granite, on the other hand,

is iron and magnesium-poor and so only very, very, very rarely contains

olivine. There are some chemical reasons for this, but I can't

tell you on this website or else my students will know the answer

before they get to the outcrop. One big part of fieldtrips with

me is learning to make careful observations. The other big part

of fieldtrips with me, though, is thinking about rocks in terms of

process while you're on the outcrop.

This outcrop is half red and half

gray. What causes this difference?

This outcrop is half red and half

gray. What causes this difference?

Lunchtime!

Lunchtime! Mylonite is a layered rock that

forms by crushing of the mineral grains when the rock is sheared.

The two main zones of the Adirondack region are separated by a mylonite

zone, suggesting one of the zones slid down along a shear zone from a

different place.

Mylonite is a layered rock that

forms by crushing of the mineral grains when the rock is sheared.

The two main zones of the Adirondack region are separated by a mylonite

zone, suggesting one of the zones slid down along a shear zone from a

different place.  Andy points out the direction of

the lineation in the mylonite.

Andy points out the direction of

the lineation in the mylonite.

Proud of their oriented sample,

Josh and Andy pose by their treasure. An oriented sample is one

which the geologist carefully records the orientation of before

bagging. This allows the geologist to orient the sample in the

exact same direction, tilt, etc. back in the lab. Some mineral

textures tell us the direction a rock was smeared/squished/etc.

We need to be able to analyze those mineral textures knowing their

orientation!

Proud of their oriented sample,

Josh and Andy pose by their treasure. An oriented sample is one

which the geologist carefully records the orientation of before

bagging. This allows the geologist to orient the sample in the

exact same direction, tilt, etc. back in the lab. Some mineral

textures tell us the direction a rock was smeared/squished/etc.

We need to be able to analyze those mineral textures knowing their

orientation!

Cooling off in Cranberry Lake

after a day of rock study. The temperature was actually quite

cool, but a dip in a mountain lake is tough to pass up!

Cooling off in Cranberry Lake

after a day of rock study. The temperature was actually quite

cool, but a dip in a mountain lake is tough to pass up!

It's good to wake up early so you

can see the sun rise.

It's good to wake up early so you

can see the sun rise.

The world is an incredibly

beautiful place, isn't it?

The world is an incredibly

beautiful place, isn't it? Migmatite is a rock that forms

when rocks are buried so deeply and heated so much that they start to

melt. The liquid migrates into swirly zones like the ones Dana's

modeling here.

Migmatite is a rock that forms

when rocks are buried so deeply and heated so much that they start to

melt. The liquid migrates into swirly zones like the ones Dana's

modeling here.  A basalt dike cuts across a

meionitic marble in the northwest Adirondacks. Rocks in the

northwest Adirondack lowlands are mostly metamorphosed sedimentary

rocks. The basalt formed much, much later when molten magma

injected into fractures. Such basalt dikes are commonly

associated with rifting, although I don't know if this particular dike

formed during the Neoproterozoic rifting, or the late Triassic rifting

event.

A basalt dike cuts across a

meionitic marble in the northwest Adirondacks. Rocks in the

northwest Adirondack lowlands are mostly metamorphosed sedimentary

rocks. The basalt formed much, much later when molten magma

injected into fractures. Such basalt dikes are commonly

associated with rifting, although I don't know if this particular dike

formed during the Neoproterozoic rifting, or the late Triassic rifting

event.

The Train Wreck - a very famous

outcrop in the Adirondack region. The dark blocks of garnet were

once a cotinuous, albeit brittle bed of rock. The surrounding

gray swirly stuff is marble. In metamorphic temperatures and

pressures, the marble flows like toothpaste, but the brittle garnet

fractures into pieces, which are smeared out to to geologic forces.

The Train Wreck - a very famous

outcrop in the Adirondack region. The dark blocks of garnet were

once a cotinuous, albeit brittle bed of rock. The surrounding

gray swirly stuff is marble. In metamorphic temperatures and

pressures, the marble flows like toothpaste, but the brittle garnet

fractures into pieces, which are smeared out to to geologic forces. Glacial striations formed when the

giant continental glacier of the last ice age scraped across these

rocks 20,000 years ago. The scratches tell the direction the ice

was flowing.

Glacial striations formed when the

giant continental glacier of the last ice age scraped across these

rocks 20,000 years ago. The scratches tell the direction the ice

was flowing. The Steer's Head outcrop - studing

chemical reaction rims that form when rocks of different compositions

are in contact with one another during metamorphism. Students

here must first identify the minerals present and then deduce what

chemical reactions took place. Again, I can't tell you the answer

right here in case future students are reading this!

The Steer's Head outcrop - studing

chemical reaction rims that form when rocks of different compositions

are in contact with one another during metamorphism. Students

here must first identify the minerals present and then deduce what

chemical reactions took place. Again, I can't tell you the answer

right here in case future students are reading this!

Close-ups of the reaction rims

Close-ups of the reaction rims

Talking about the Balmat zinc

deposit with Bill DeLorraine - a geologist working at the mine.

Bill's incredibly sharp - the folks at HudBay Minerals, Inc. are lucky

to have such a smart and experienced guy working for them. Here,

the class poses by the three dimensional mine model that shows the ways

the orebodies twist and turn deep underground. We were not able

to tour underground, though, because the mine was closed down.

The Balmat mine, being a smaller mine, must open and close depending on

the price of zinc metal. Opening and closing a mine's opperations

is an expensive endeavor, so it's not a decision made lightly.

They keep the mine pumped dry, though, during the time they're closed

down, which dramatically reduces the start up costs.

Talking about the Balmat zinc

deposit with Bill DeLorraine - a geologist working at the mine.

Bill's incredibly sharp - the folks at HudBay Minerals, Inc. are lucky

to have such a smart and experienced guy working for them. Here,

the class poses by the three dimensional mine model that shows the ways

the orebodies twist and turn deep underground. We were not able

to tour underground, though, because the mine was closed down.

The Balmat mine, being a smaller mine, must open and close depending on

the price of zinc metal. Opening and closing a mine's opperations

is an expensive endeavor, so it's not a decision made lightly.

They keep the mine pumped dry, though, during the time they're closed

down, which dramatically reduces the start up costs.

Hunting for marble outcrops in the

Adirondack jungle.

Hunting for marble outcrops in the

Adirondack jungle.

Some strange features in the

marble. The locations of these features is a secret - they are

pretty incredible and should not be disturbed, as you well know if you

recognize what they are!

Some strange features in the

marble. The locations of these features is a secret - they are

pretty incredible and should not be disturbed, as you well know if you

recognize what they are!