Brief outline of Pennsylvania’s Geologic History

Kurt Friehauf

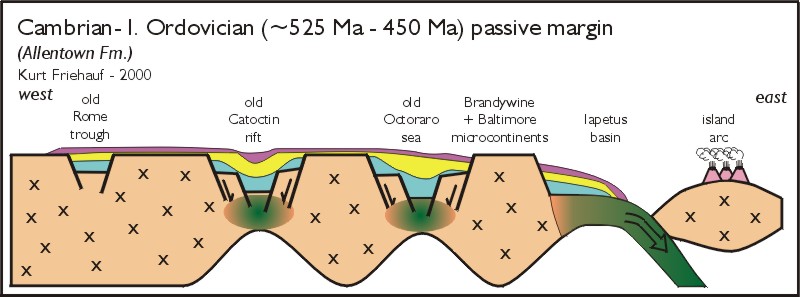

525-450 million years ago – Cambrian-Ordovician passive margin stage

Once the continent split up, there was a long quiet period during which the mountains continued to erode down. Sediment from erosion of the old Grenville Mountains washed into the basins, forming thick piles of sedimentary rocks. Some of these sediments were coarse-grained fragments of quartz and feldspar – such sediment was eventually glued together to form sedimentary rocks such as conglomerate, sandstone, and shale. Off the coast in slightly deeper marine waters, limestone deposits formed which would eventually play a crucial role in the industrial revolution in the U.S.

But although things were quiet here in North America, the Earth’s tectonic plates were more active further east. Far out to sea, the thin tectonic plate that underlay the ocean cracked and the rocks on east side of the crack began to slip beneath the rocks on the west side. When one tectonic plate slides beneath another, geologists call the process “subduction.” Subduction has several effects on the Earth. Subduction produces lots of earthquakes as the two plates rub past one another (that’s why there are earthquakes in Japan, Taiwan, Philippines, western South America, and Central America). Subduction also causes deep rocks to melt, forming hot, molten magma that can rise to the surface and form volcanoes. In some cases, when one oceanic plate slips beneath another oceanic plate, these volcanoes form strings of islands called “volcanic island arcs,” like Japan, Taiwan, Philippines, and Indonesia). In other cases, an oceanic plate slips beneath a continental plate, forming high volcanic mountains like the Andes of western South America and the Cascade Mountains of Washington and Oregon (Mount Saint Helens and friends).

In this case, the subduction formed an island arc in the ocean east of North America.

Click here to move on to the next stage